Plastic waste management and carbon accountability are increasingly influencing material selection across industries. Bioplastics—polymers derived partially or entirely from renewable biomass—are gaining attention not only for their environmental potential but also for their functional performance in modern manufacturing. Understanding what bioplastics are, how they differ from conventional plastics, and where their real advantages lie is essential for informed material decisions.

Compared with petroleum-based plastics, bioplastics can offer several structural and lifecycle advantages, including reduced fossil carbon dependence, diversified raw material sources, and in some cases improved end-of-life pathways. However, their environmental value is not universal; it depends on feedstock origin, formulation, processing, and disposal conditions.

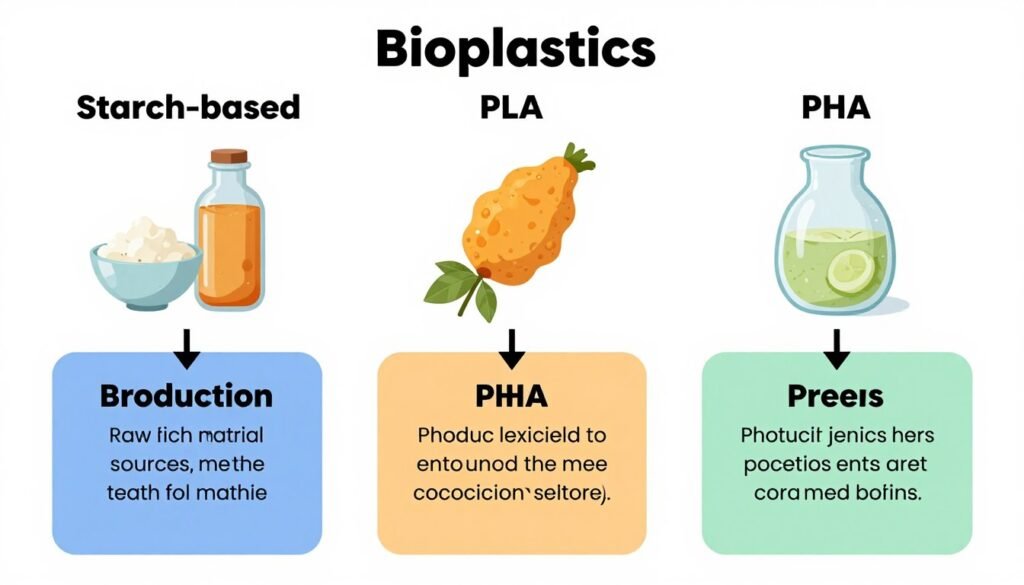

Three Main Categories of Bioplastics

From a material sourcing and application engineering perspective, three bioplastic families currently dominate commercial supply chains: Starch-Based Plastics, Polylactic Acid (PLA), and Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA).

Each category differs in feedstock origin, processing behavior, mechanical performance, and end-of-life pathways. Understanding these distinctions is essential for selecting suitable resin grades for specific industrial applications rather than evaluating materials based solely on biodegradability claims.

The three main categories of bioplastics and their source materials

Starch-Based Bioplastics

Starch-based bioplastics represent one of the earliest and most commercially accessible segments of biodegradable plastics. They are derived from renewable plant sources rich in starch, such as corn, potatoes, wheat, or cassava, and are widely used in flexible packaging and agricultural applications.

Common starch-based bioplastic products including packaging peanuts and food containers

Production Process

Starch-based materials are produced by extracting starch and transforming it into thermoplastic starch (TPS) through gelatinization and plasticization. Because native starch is brittle, plasticizers such as glycerol or sorbitol are introduced to improve flexibility and melt processability. TPS compounds can be processed using conventional equipment including extrusion, film blowing, and injection molding.

Modern modified starch blends are often compounded with biodegradable polyesters to enhance mechanical strength and moisture resistance.

Key Properties

- Biodegradable under controlled composting conditions

- Renewable feedstock origin

- Moisture-sensitive without modification

- Lower inherent mechanical strength compared to conventional plastics

- Compatible with blending and compounding technologies

Common Applications

- Loose-fill packaging

- Compostable bags

- Agricultural mulch films

- Disposable food service items

- Flexible packaging films

For a comprehensive overview of starch-based biodegradable plastics, including their material properties, real-world applications, and commercial challenges, see our detailed article: Starch Based Biodegradable Plastics: Materials, Applications, and Commercial Reality.

Limitations

Performance limitations primarily relate to humidity sensitivity and structural strength. However, advanced compounding techniques and polymer blending have enabled starch-based materials to meet regulated packaging requirements in many sectors.

Polylactic Acid (PLA)

Polylactic Acid (PLA) is one of the most established and widely distributed bioplastics in industrial markets. Produced from fermented plant sugars followed by polymerization, PLA benefits from a mature global production infrastructure and broad resin grade availability.

PLA bioplastic products showing transparency and versatility in applications

Production Process

PLA production begins with converting plant-derived starch or sugar into lactic acid via fermentation. The lactic acid is then polymerized into long molecular chains forming PLA resin. The resulting polymer can be processed using standard plastic manufacturing systems such as extrusion, thermoforming, fiber spinning, and filament production.

Key Properties

- Transparent appearance comparable to polystyrene

- Good rigidity and tensile strength

- Industrially compostable (typically above 58–60 °C)

- Moderate heat resistance

- Excellent printability and dimensional stability

Common Applications

- Food packaging and rigid containers

- Disposable tableware

- 3D printing filaments

- Textile fibers and nonwovens

- Certain biomedical and implantable devices

For a detailed exploration of PLA’s biodegradability and sustainability aspects, see our in-depth guide: Is PLA Biodegradable? The Ultimate Guide to Sustainable Plastics.

Limitations

PLA softens at relatively low temperatures and exhibits limited gas barrier performance compared to some petroleum-based plastics. Effective biodegradation generally requires industrial composting infrastructure rather than home compost or natural soil environments.

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA)

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are a family of biopolyesters synthesized directly by microorganisms through bacterial fermentation of sugars or lipids. Unlike many other bioplastics, PHAs are produced as natural intracellular energy reserves, making them fully bio-synthesized polymers.

PHA bioplastic applications in medical devices and specialty packaging

Production Process

PHA production involves cultivating specific bacterial strains under nutrient-limited conditions that trigger polymer accumulation. After fermentation, the polymer is extracted and purified. More than 150 monomer variations can be incorporated into PHA structures, allowing significant tunability in flexibility, toughness, and degradation rate.

Key Properties

- Biodegradable across diverse environments, including soil and marine settings

- Water-resistant compared to many other bioplastics

- Biocompatible for medical and pharmaceutical uses

- Adjustable mechanical properties through formulation

- Suitable for specialty coatings and compounding

Common Applications

- Medical sutures and implants

- Marine-degradable packaging

- Agricultural films

- Adhesives and coatings

- Specialty 3D printing materials

For a deeper insight into PHA’s evolving role in sustainable materials and its broad application landscape, see our detailed article: Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA): The Future and Applications of Green Plastics.

Limitations

Commercial adoption of PHAs is influenced by production cost, processing stability, and scale efficiency. Ongoing advancements in fermentation optimization and feedstock utilization continue to improve cost-performance alignment and material consistency.

Practical Material Selection Perspective

In practice, these three material families often coexist within product portfolios, each addressing different performance targets, regulatory requirements, and sustainability objectives.

Material selection typically depends on processing method, mechanical expectations, certification standards, supply availability, and end-of-life scenarios, rather than biodegradability alone.

Real-World Applications: Which One is Suitable for Your Product?

Bioplastic selection hinges on matching specific performance criteria and end-of-life requirements to your product needs. With a diverse range of resin grades and expert guidance, we help you optimize material choice for every application.

Real-world applications of bioplastics across different industries

| Material | Key Properties | Common Applications | Ideal for Products Like: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starch-Based | Biodegradable under industrial composting, water-sensitive, moderate strength, opaque appearance | Flexible packaging, disposable items, agricultural films | Packaging peanuts, compost bags, disposable cutlery, short-term packaging |

| PLA (Polylactic Acid) | Transparent, rigid, good printability, industrially compostable, moderate heat resistance | Food packaging, 3D printing, disposable tableware, textiles | Clear food containers, cold drink cups, bakery packaging, 3D printed prototypes |

| PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoates) | Biodegradable in various environments including marine, water-resistant, biocompatible, versatile properties | Medical devices, marine-degradable packaging, specialty packaging | Medical implants, marine-degradable packaging, premium compostable items |

Starch-based materials and PLA are ideal choices for short-term, compostable packaging when industrial composting facilities are accessible. PHA stands out for applications demanding marine biodegradability and biocompatibility, offering performance advantages beyond conventional bioplastics.

Selecting the right bioplastic requires careful consideration of local waste management infrastructure and certification standards to ensure your sustainability goals are met throughout the product lifecycle.

Explore Sustainable Material Options for Your Products

We supply reliable, high-quality bioplastic raw materials tailored to your needs.

Contact us today to discuss how we can support your supply chain and help you find the best bioplastic solutions for your applications.

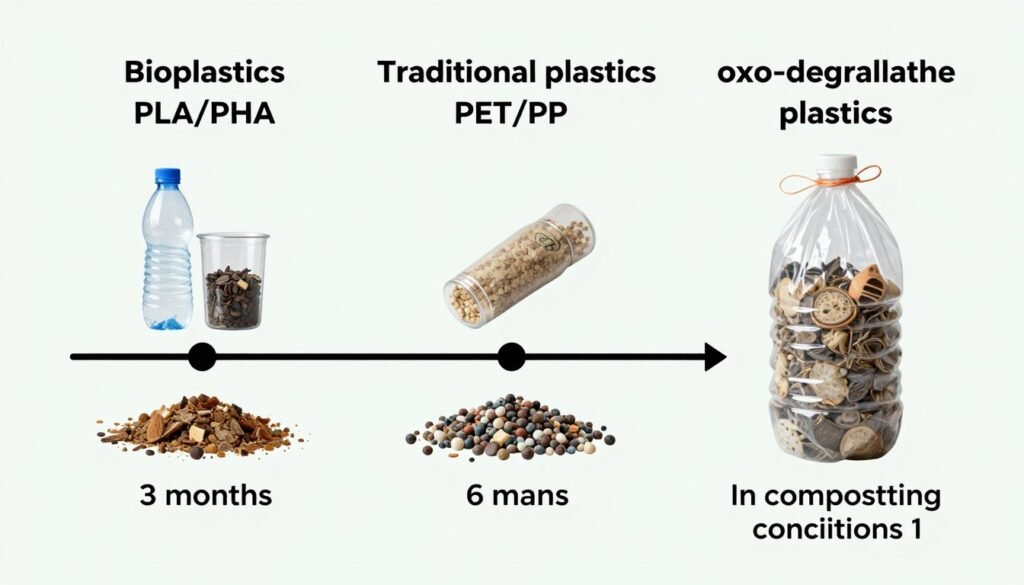

Bioplastics vs. Traditional Plastics vs. Ordinary Biodegradable Plastics

Understanding the key differences among various plastic types is essential for making informed material choices. The following comparison highlights the distinctions between bioplastics (PLA, PHA, starch-based), traditional petroleum-based plastics, and additive-based degradable plastics such as oxo-degradable types.

Degradation comparison between different plastic types under composting conditions

| Feature | Bioplastics (PLA/PHA/Starch) | Traditional Plastics (PET, PP) | Additive-Based Degradable Plastics (Oxo-degradable) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Source | Renewable biomass (corn, sugarcane, bacteria) | Fossil fuels (petroleum) | Fossil fuels with degradation additives |

| Biodegradability | Varies by type; many biodegrade under specific conditions | Not biodegradable; persists for hundreds of years | Fragment into microplastics; not truly biodegradable |

| Degradation Conditions Required | PLA requires industrial composting (60°C+); PHA can degrade in marine environments; starch-based biodegrades under industrial composting | Does not biodegrade; degrades only by UV and mechanical processes over centuries | Degrades under UV exposure and oxygen but remains as microplastics |

| Compostable (Industrial/Home) | Many industrially compostable; few suitable for home composting | Not compostable | Not truly compostable; leaves microplastic residue |

| Typical End-of-Life Options | Industrial composting, recycling (for some), landfill | Recycling, incineration, landfill | Landfill, incineration (recycling not recommended) |

| Carbon Footprint | Generally lower; captures atmospheric carbon during plant growth | Higher; releases fossil carbon | Similar to traditional plastics |

| Cost Comparison | Generally higher (1.5-4x traditional plastics) | Lower (baseline) | Slightly higher than traditional plastics |

Each bioplastic type offers unique advantages:

- PLA provides clarity and good processability, making it ideal for food packaging and disposable items.

- PHA stands out for its biodegradability in diverse environments, including marine settings, making it suitable for medical devices and specialty packaging.

- Starch-based plastics offer cost-effective solutions for short-term applications such as compostable bags and agricultural films.

We provide consistent supply and expert technical support to help you select the best bioplastic materials that align with your sustainability goals and processing requirements.

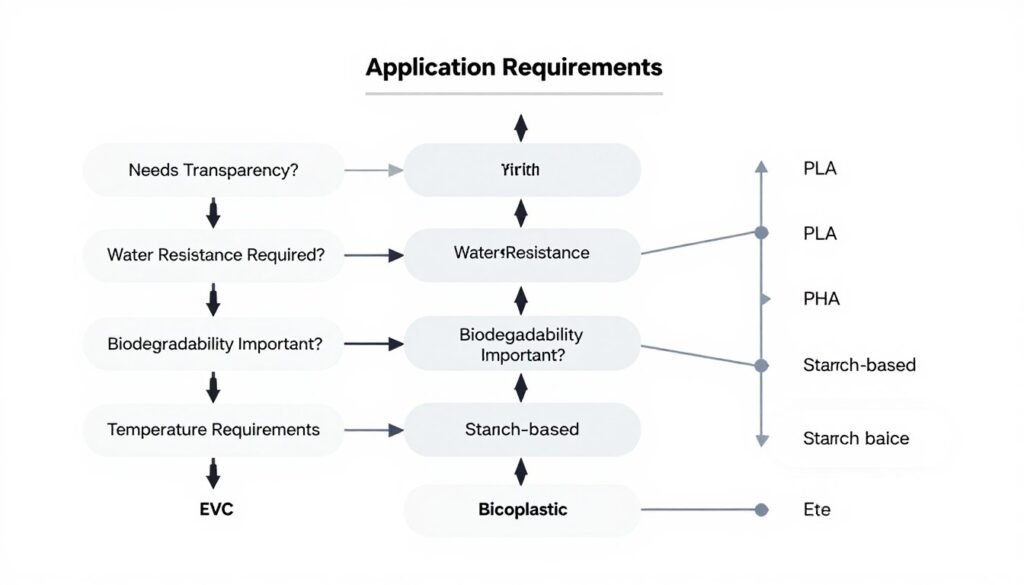

Conclusion: How to Choose the Right Bioplastic for You

Choosing the appropriate bioplastic involves careful consideration of multiple factors to ensure the best fit for your application:

Decision flowchart for selecting the appropriate bioplastic based on application requirements

Consider Product Requirements

- Mechanical properties (strength, flexibility)

- Barrier properties (moisture, oxygen)

- Transparency requirements

- Temperature resistance

- Expected product lifespan

Evaluate End-of-Life Scenarios

- Availability of industrial composting facilities

- Potential for recycling

- Importance of marine biodegradability

- Local waste management infrastructure

- Consumer disposal behavior

Assess Practical Considerations

- Cost constraints and budget

- Compatibility with manufacturing processes

- Regulatory compliance

- Supply chain reliability

- Carbon footprint goals

No single bioplastic fits all purposes. For short-use food packaging, compostable materials like PLA and starch-based bioplastics are ideal. Durable goods may benefit from bio-based, non-biodegradable options such as Bio-PE. For medical or specialty applications requiring biocompatibility and marine degradability, PHA is often the superior choice.

Bioplastic technology continues to advance, with new materials offering improved performance and cost efficiency. Staying informed about these developments helps businesses remain competitive and sustainable.

We provide reliable supply and technical expertise to help you select and source the best bioplastic materials tailored to your specific needs. Contact us to learn how we can support your sustainability and performance goals.

Looking for the Right Bioplastic Material?

Access our expertise on PLA, PHA, and starch-based bioplastics, with insights on properties and processing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are answers to some common questions about bioplastics and their applications.

Common questions and misconceptions about bioplastics

What is bioplastic in simple words?

Bioplastics are plastics that are either made from renewable biological sources (like plants) instead of petroleum, or are biodegradable, or both. They’re designed to have a lower environmental impact than conventional plastics while still providing similar functionality.

Why are bioplastics bad for the environment?

While bioplastics generally have environmental advantages over conventional plastics, they aren’t without drawbacks. Some concerns include land use for growing feedstocks, potential for food competition, higher eutrophication and acidification potentials from agricultural practices, and improper disposal. Many bioplastics require specific industrial composting conditions to biodegrade properly and won’t break down in natural environments or landfills.

What are the three types of bioplastics?

The three main types of bioplastics are:

- Starch-based bioplastics – Made from corn, potato, or other starch sources

- PLA (Polylactic Acid) – Produced from fermented plant sugars, commonly corn or sugarcane

- PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoates) – Created by bacterial fermentation of sugars or lipids

Is bioplastic 100% biodegradable?

Not all bioplastics are biodegradable. Some bioplastics, like bio-PE and bio-PET, are chemically identical to their petroleum-based counterparts and are not biodegradable despite being made from renewable resources. Even biodegradable bioplastics often require specific conditions (like industrial composting facilities) to properly break down, and the biodegradation timeframe varies significantly between different bioplastic types.

How are bioplastics made?

Bioplastics are made through various processes depending on the type:

- Starch-based bioplastics are made by extracting starch from plants, processing it with plasticizers, and forming it into the desired shape.

- PLA is produced by fermenting plant sugars to create lactic acid, which is then polymerized into long molecular chains.

- PHA is created by bacterial fermentation where microorganisms produce the polymer as energy storage under specific nutrient conditions.

After production, bioplastics can be processed using many of the same manufacturing techniques as conventional plastics, including injection molding, extrusion, and thermoforming.

What are bioplastics used for?

Bioplastics have diverse applications across multiple industries:

- Packaging – Food containers, bags, films, bottles

- Consumer goods – Disposable cutlery, straws, cups

- Agriculture – Mulch films, plant pots

- Textiles – Fibers and fabrics

- Medical – Implants, sutures, drug delivery systems

- Automotive – Interior components

- 3D printing – Filaments and resins

The specific application depends on the properties of the particular bioplastic type.

What are bioplastics made of?

Bioplastics can be made from various renewable resources:

- First-generation feedstocks: Food crops like corn, sugarcane, cassava, and vegetable oils

- Second-generation feedstocks: Non-food biomass like agricultural waste, wood chips, and cellulosic materials

- Third-generation feedstocks: Algae and other non-land using resources

Some bioplastics are also produced by microorganisms through fermentation processes.