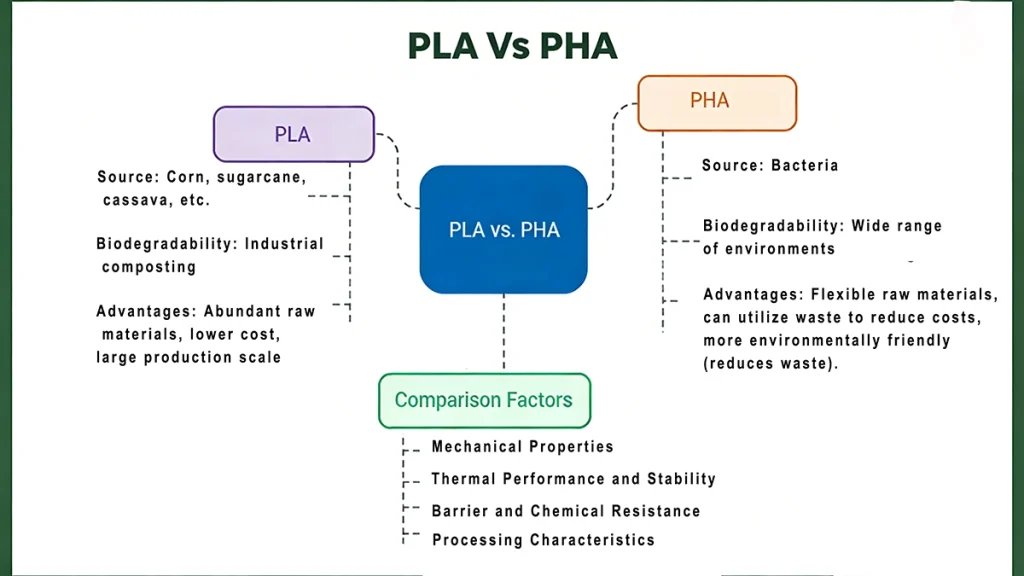

PLA and PHA are frequently grouped together under the label of “bioplastics,” yet treating them as interchangeable resins continues to cause costly mistakes in real manufacturing environments. Differences in melt behavior, thermal stability, mechanical performance, and certified end-of-life pathways directly affect tooling performance, cycle stability, product compliance, and long-term sourcing risk.From the material selection and resin distribution experience of Sales Plastics, misalignment between application requirements and biopolymer choice remains one of the most common root causes behind failed sustainability-driven product launches.

This article compares PLA and PHA from a practical material-selection and sourcing standpoint, helping manufacturers align performance requirements, processing capability, and sustainability targets before committing to production-scale purchasing.

The Fundamentals: Sources, Chemistry, and Production

PLA and PHA differ fundamentally in how their polymer chains are formed, and this distinction drives their performance consistency, processing behavior, and commercial scalability.

PLA: Monomer Synthesis and Polymerization

Polylactic Acid (PLA) is produced through controlled chemical polymerization of plant-derived lactic acid, typically sourced from corn starch or sugarcane. This chemical route allows precise control over molecular weight, stereochemistry, and crystallinity, enabling standardized grades, predictable processing windows, and large-scale global supply across multiple melt flow ranges.

PLA production process: from corn or sugarcane to finished bioplastic

PHA: Microbially Produced Polymer

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA), by contrast, is synthesized biologically by microorganisms that convert carbon feedstocks into intracellular polyester chains. Polymer structure varies with microbial pathways and feedstock selection, resulting in a broad family of materials whose mechanical properties, thermal stability, and melt behavior can differ significantly between grades and suppliers.

PHA production through bacterial fermentation and extraction processes

These distinct production pathways explain why PLA behaves as a highly consistent, engineering-oriented biopolymer, while PHA offers greater functional tunability at the cost of increased variability in processing conditions and commercial availability.

Chemical Structure Comparison

| Property | PLA | PHA |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Origin | Chemically polymerized from lactic acid | Biologically synthesized by microorganisms |

| Structure Control | High; stereochemistry and crystallinity are tunable | Variable; dependent on microbial pathway and feedstock |

| Crystallinity Tendency | Adjustable from amorphous to semi-crystalline | Generally high for common homopolymers |

| Commercial Consistency | High; standardized, widely available grades | Lower; grade- and supplier-dependent variability |

PLA vs PHA: Technical Performance and Properties Comparison

When specifying PLA and PHA, understanding their inherent performance profiles is essential for aligning material capabilities with application demands. The molecular architecture of each polymer directly dictates its mechanical, thermal, and barrier functionality.

Sustainable Polymers Comparison: Core Attributes of PLA vs. PHA

Mechanical Properties

PLA typically acts as a rigid, high-strength polymer, while PHA exhibits greater versatility, ranging from stiff to highly ductile.

| Property | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) | Implication for Material Specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | High and consistent | Variable, from moderate to low | PLA suits rigid, load-bearing parts; PHA offers flexibility |

| Ductility / Flexibility | Stiff and brittle | Broad range from flexible to tough | Choose PHA for flexible or impact-resistant items |

| Elongation at Break | Low (~2–10%) | Wide range (up to elastomeric levels) | PHA better for products requiring high elongation |

Thermal Performance and Stability

Temperature characteristics determine both the materials’ processing window and their suitability for end-use environments (e.g., hot liquids or freezing conditions).

| Property | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) | Implication for Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Transition Temp. (Tg) | Moderate (55–65℃) | Low (-50℃ to 5℃) | PHA offers better flexibility at low temperatures |

| Heat Deflection Temp. (HDT) | Low to moderate (~55–60℃) | Variable, sometimes higher with treatment | PLA needs post-processing for heat-exposed applications |

| Melting Point (Tm) | 170–180℃ | Broad range (80–180℃) | PHA’s melting varies with composition, affecting processing |

Barrier and Chemical Resistance

For packaging, barrier properties—the resistance to mass transfer—are paramount for preserving product shelf life.

| Barrier Property | Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) | Packaging Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Barrier | Moderate | Good to excellent | PHA preferred for oxygen-sensitive packaging |

| Water Vapor Barrier | Poor to moderate | Generally better | Both may need coatings for high moisture resistance |

| Oil/Grease Resistance | Good | Acceptable but variable | PLA better for fatty or oily food containers |

Processing Characteristics

The ease and efficiency of manufacturing are crucial for commercial viability.

PLA Processing

- High compatibility with standard thermoplastic equipment.

- Wide processing window (e.g., Injection Molding 170–210℃).

- Excellent suitability for Thermoforming and 3D printing (FDM).

PHA Processing

- Requires a narrower, lower temperature window (130–180℃).

- Highly sensitive to thermal degradation and shear heat, demanding rigorous parameter control.

- Specialized tuning is required to manage its variable melt viscosity.

The sensitivity of PHA to thermal degradation means processing often requires low residence time and precise temperature control, posing a higher entry barrier for manufacturers accustomed to conventional resins.

Need detailed specs to choose the right bioplastic?

Contact us to get a comprehensive PLA vs PHA report with full technical data—designed to simplify your material selection.

End-of-Life: Biodegradability and Environmental Impact

The environmental credentials of bioplastics are central to their value proposition, but significant differences exist in how PLA and PHA interact with and break down in various end-of-life environments.

Industrial Composting vs Home Composting

Biodegradation Mechanisms and Timeframes

The primary difference lies in the degradation pathway. PLA degradation begins with hydrolysis—the chemical breakdown by water—which is greatly accelerated by elevated temperatures (≥58°C) and humidity, allowing subsequent microbial consumption of the resulting oligomers. In contrast, PHA is produced by microorganisms and is more readily recognized and enzymatically degraded by a wide range of bacteria and fungi, even under ambient conditions.

| Environment | PLA | PHA | Key Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial Composting | 3–6 months (needs high heat ≥58℃) | 1–3 months (faster under optimal conditions) | Both suitable for industrial composting, but PLA requires strict heat control. |

| Home Composting | Very slow to negligible | 3–12 months (many certified grades) | PHA supports practical home composting; PLA does not. |

| Soil & Marine | Very slow or negligible | 3–12 months or more (certified grades) | PHA biodegrades effectively in natural environments, PLA does not. |

Certification Standards

Certification is the technical proof of an end-of-life claim.

PLA Certifications

- Certified for Industrial Composting (ASTM D6400, EN 13432).

- Not typically certified for home composting, soil, or marine environments due to slow degradation.

PHA Certifications

- Certified for Industrial Composting (ASTM D6400, EN 13432).

- Many commercial grades certified for Home Composting (OK Compost HOME)

- Soil, and Marine Biodegradation (OK biodegradable SOIL/MARINE).

💡 Further Reading: For information on the unique degradation mechanisms of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) in marine and soil environments, their molecular tunability, and their applications in the PHA portfolio, please refer to our “A Comprehensive Guide to Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs),” which provides detailed technical specifications and commercial solutions.

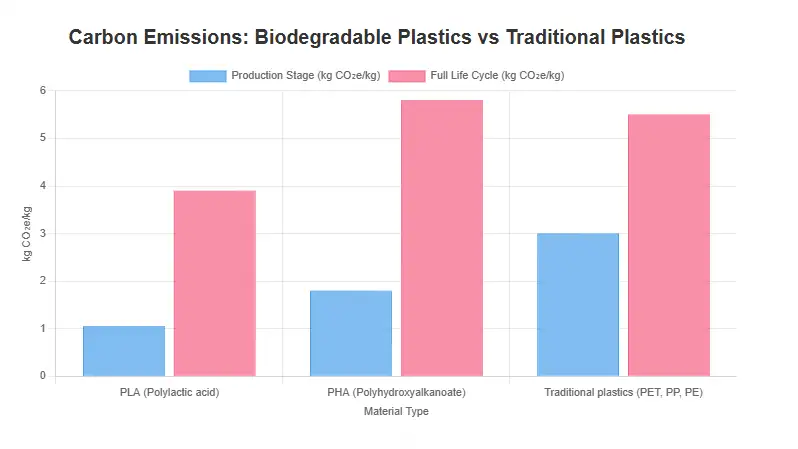

Carbon Footprint Comparison

The overall environmental profile requires a full Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), moving beyond just biodegradability.

Carbon Emission Comparison: Biodegradable Plastics (PLA, PHA) vs. Traditional Plastics (PET, PP, PE)

PLA Environmental Advantages

- Lower energy consumption per unit (due to scale).

- Reduced net CO₂ (due to biogenic carbon content).

- Established commercial scale and production efficiency.

PLA Environmental Challenges

- End-of-life constrained by limited industrial composting infrastructure.

- Feedstock reliance on food-competing crops (e.g., corn).

- Slow degradation in natural, ambient environments.

PHA Environmental Advantages

- Verified biodegradability in soil and marine environments.

- Ability to use diverse feedstocks, including waste streams.

- Mitigates pollution risk through effective natural degradation.

PHA Environmental Challenges

- Higher per-unit energy input (due to smaller scale).

- Historically, some extraction uses solvents (though shifting).

- Higher cost limits rapid, widespread adoption.

🔎 In-depth analysis: Is PLA truly sustainable plastic? To gain a more comprehensive understanding of PLA’s environmental commitments, actual degradation conditions, supply chain challenges, and how to mitigate potential “green wash” risks, please refer to our “Is PLA Biodegradable? The Ultimate Guide to Sustainable Plastics“.

Practical Applications and Decision-Making

Determining the optimal bioplastic requires a strategic assessment that balances technical performance, environmental accountability, and commercial economics for specific end-use applications.

Industry-Specific Applications

The functional divergence between PLA and PHA dictates their suitability across various sectors:

Commercial applications of PLA and PHA bioplastics across multiple industries

Food Packaging

Agricultural Products

Medical Applications

Consumer Goods

3D Printing

Disposable Items

Cost Considerations

Economic factors often play a decisive role in material selection:

| Cost Factor | PLA | PHA |

| Raw Material Cost | $2.2-3.2/kg | $4-7/kg |

| Production Scale | Large commercial scale | Smaller scale, growing |

| Processing Complexity | Similar to conventional plastics | More specialized, potentially higher |

| Future Price Trend | Stable to decreasing | Decreasing as scale increases |

Prices are subject to market fluctuations. Please contact us for the latest quotation.

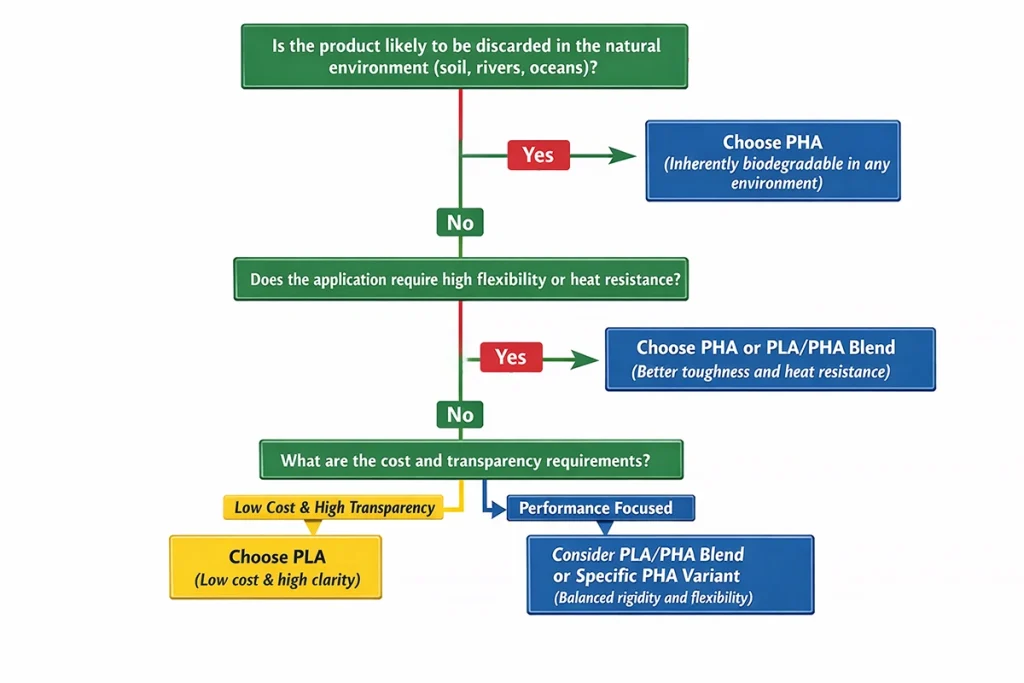

Decision Framework

A rigorous, systematic approach minimizes risk and maximizes the return on investment in sustainable materials:

PLA vs PHA Material Selection Decision

Conclusion

Determining the optimal bioplastic resin involves balancing application requirements, processing capabilities, cost, and end-of-life goals.PLA delivers a mature, cost-effective solution for rigid, high-volume products. PHA stands out with greater flexibility and superior natural biodegradability, though it demands more complex processing and higher cost. Sales Plastics offers expert guidance, dependable sourcing, and support for both PLA and PHA to ensure the best material fit for your needs.

Ready to advance your bioplastic project?

Contact our experts to discuss your material requirements and find the ideal PLA or PHA resin for your application.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is PHA better than PLA?

Neither PLA nor PHA is universally “better.” Each material offers a unique set of technical and commercial advantages. PLA offers superior commercial scale, lower cost, stable processing, and excellent optical clarity. PHA provides a significant advantage in environmental accountability (verified multi-environment biodegradability), greater flexibility, and enhanced barrier properties. The optimal choice depends entirely on balancing your product’s mechanical requirements, target end-of-life environment, and economic constraints.

Is PLA a PHA?

No, PLA (Polylactic Acid) is not chemically related to the PHA (Polyhydroxyalkanoate) family. They constitute distinct classes of bioplastics. PLA is an aliphatic polyester produced via a multi-step chemical polymerization process from purified bio-monomers (lactic acid/lactide). PHA is a family of polyesters produced biologically by bacteria in vivo (inside the cell) as a natural energy storage mechanism, utilizing carbon feedstocks.